News ·

Spawning breeds new hope for the Great Barrier Reef

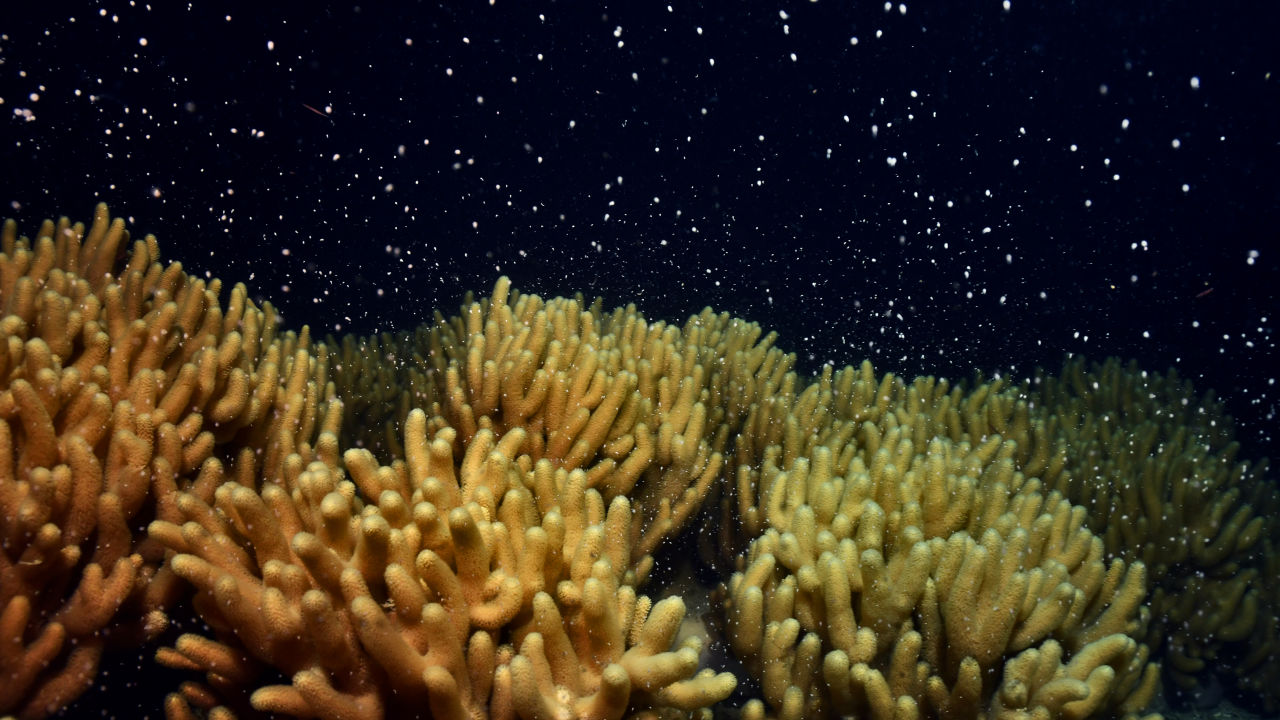

The Reef is teeming with new life after the world’s biggest reproductive event – coral spawning – which is giving new hope to reefs damaged by climate change.

Corals simultaneously reproduce at this time every year in one of the most extraordinary natural phenomena on the planet, releasing enough eggs and sperm into the water to produce trillions of baby corals. Fertilised eggs develop into baby corals, known as larvae, which settle on the ocean floor and repopulate the Reef.

This spawning event is an exciting and busy time of year for Reef scientists, providing them with an opportunity to fast-track world-leading restoration efforts.

Working together, they’re using coral spawn to pioneer new solutions that can be used to protect the reefs we have left and help them resist and adapt to warming ocean temperatures.

#Lizard Island

At Lizard Island in the far north of the Reef, Southern Cross University Distinguished Professor Peter Harrison and research partners CSIRO and QUT worked late into the night collecting spawn for a novel coral larval restoration technique known as Coral IVF.

They trialled new methods to capture coral spawn, growing many millions of larvae in floating pools.

They’re now testing different methods to efficiently deliver and settle healthy coral larvae onto reef sites that have been damaged by mass bleaching events.

Specially designed pools were used to collect and store coral larvae in the Lizard Island lagoon. Credit: SCU

Peter Harrison inspecting coral spawn. Credit: SCU

#Heron Island

Further south on Heron Island, CSIRO Senior Research Scientist Dr Christopher Doropoulos is leading a team that’s investigating how young corals respond to different interactions and disturbances during their development and settlement phases.

This helps scientists predict and test coral recovery at larger scales.

Young coral growth. Credit: Peter Harrison

#National Sea Simulator

At the Australian Institute of Marine Science (AIMS) in Townsville, hundreds of coral colonies from across the Great Barrier Reef were brought to the National Sea Simulator to replicate spawning in captivity.

Principal Research Scientist Dr Line Bay and her team kept a close eye on the spawning corals in their specialised aquaculture facility.

Breeding corals in controlled environments allows researchers to fast-track our understanding of how to enhance coral survival and growth and help corals better cope with increased seawater temperatures.

The aim is to increase the number of captive-born heat-tolerant young corals, and potentially release these onto large areas of degraded reefs in the future.

The integrated research is part of the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program, which is funded by the partnership between the Australian Government’s Reef Trust and the Great Barrier Reef Foundation. Partners include the Australian Institute of Marine Science, Great Barrier Reef Foundation, CSIRO, The University of Queensland, QUT, Southern Cross University and James Cook University.