News ·

Frozen coral sperm successfully used in coral breeding trials

A new trial using frozen sperm to grow corals has delivered an impressive 90% success rate, in further evidence that this innovative technique could be key to restoring damaged coral reefs.

Researchers hope cryopreservation, which aims to store frozen coral sperm for use in future breeding programs, will allow us to repopulate large areas of the Great Barrier Reef.

In November 2021, scientists from Taronga Conservation Society thawed frozen coral sperm samples to fertilise over 300,000 eggs spawned in the National Sea Simulator at the Australian Institute of Marine Science. Their experiments had over 90% fertilisation success rate, which matches the fertilisation rate of fresh sperm.

During spawning nights, the team are cryopreserving sperm and other living cells from many colonies from multiple species. One of the challenges is that it can take up to half an hour for sperm to start moving around after release from the coral polyp bundle, but the scientists have found an innovative solution to speed up the process and avoid delays in sample freezing that might decrease future fertility potential.

“One of the cool things that we’ve started doing is using caffeine to activate a representative sample of coral sperm from each colony. This allows us to rapidly assess their quality and cryopreserve the remaining sample while it is as fresh as possible” says lead researcher Dr Jonathan Daly, Taronga Conservation Society.

Senior research scientists Dr Jonathan Daly, Taronga Conservation Society, and Dr Line Bay, Australian Institute of Marine Science, collect eggs during coral spawning in the National Sea Simulator at the Australian Institute of Marine Science.

How is coral sperm cryopreserved?

When corals spawn, they release bundles of sperm and eggs. Researchers collect these bundles, separate the sperm and immediately place it in liquid nitrogen at a chilly -196 degrees Celsius.

The frozen coral sperm are then placed in travel-safe containers of nitrogen vapour and shipped to “seed banks” at Taronga Zoo Sydney on Cammeraigal Country, and at Taronga Western Plains Zoo in Dubbo on Wiradjuri Country. There they are cared for in biosecure and alarmed chambers of liquid nitrogen.

At -196 degrees Celsius, metabolic processes stop and the cells can be kept frozen in that state indefinitely. When they’re needed for future Reef restoration efforts, different types of warming and thawing methods are used to revive them.

Cryobiologists around the world have proved that using cryopreserved sperm produces healthy, viable coral babies. This provides further evidence that the technique is a powerful tool in generating extra stocks of new corals that could re-populate the Reef as needed.

Additionally, using cryopreserved samples of corals from a wide range of locations will help restoration scientists to maintain the genetic diversity of repopulated reefs. Now, the focus is on building a diverse collection of frozen high conservation value coral species found along the length of the Great Barrier Reef.

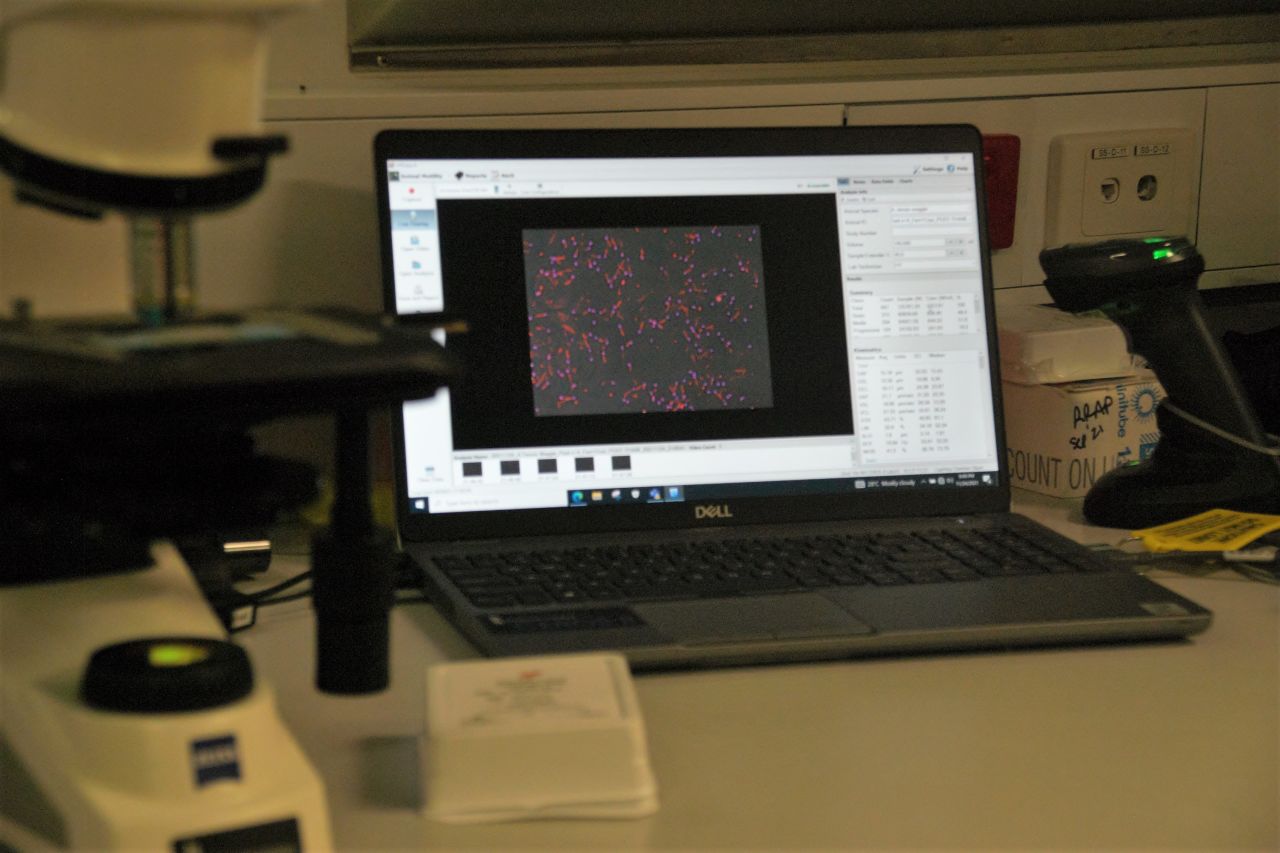

Coral sperm is viewed under microscope using specialised computer programs to assess activation.

The work is part of the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program, funded by the partnership between the Australian Government's Reef Trust and the Great Barrier Reef Foundation.

Top image: Cryobiologist Dr Rebecca Hobbs, Taronga Conservation Society, cryopreserving coral sperm and egg samples and placing in chambers of liquid nitrogen. Credit: Dorian Tsai