Explainers ·

What is coral cryopreservation?

What it is, why we do it and how it’s helping restore damaged coral reefs.

To watch corals spawning is to witness one of the great wonders of the natural world. Hundreds of thousands of corals releasing their eggs and sperm into the water in a synchronised symphony of reproduction.

Spawning happens just once or twice a year and for researchers who rely on coral spawn to help grow and plant new corals onto damaged areas of the Reef, such a short season can be very limiting.

This is where coral cryopreservation can help, ensuring cells like coral sperm can be safeguarded and utilised in the future reproduction efforts of corals.

#How does coral cryopreservation work?

Coral cryopreservation is the process of preserving coral cells and tissues at very low temperatures.

Like all animal cells, coral cells and tissues contain lots of water which, when frozen, form ice crystals that can cause damage. Cryopreservation techniques aim to minimise ice crystal formation and keep corals and their cells alive while they’re being frozen. This is done by adding what’s known as cryoprotectants, which remove water from the cells while they’re being frozen and also support cell structures when samples are thawed.

Taronga’s CryoDiversity Bank at the Taronga Institute of Science and Learning. Credit J. K. O’Brien

#What is the process of cryopreservation?

Samples of egg and sperm bundles are collected from spawning corals at the National SeaSimulator operated by the Australian Institute of Marine Science. After sperm are separated from eggs, the sperm are immediately cryopreserved and transferred to liquid nitrogen at a chilly -196 degrees Celsius.

Frozen coral sperm, along with fertilised eggs that have turned into larvae, are then placed in travel-safe containers of nitrogen vapour and shipped to “seed banks” at Taronga Zoo Sydney on Cammeraigal Country, and at Taronga Western Plains Zoo in Dubbo on Wiradjuri Country.

There they are stored in biosecure and alarmed chambers of liquid nitrogen at -196 degrees Celcius. At that temperature, metabolic processes stop and the cells can be kept frozen in that state indefinitely. When they’re needed for future reef restoration efforts, different types of warming and thawing methods are used including laser warming technology for coral larvae.

Corals exist in many different forms across their life span, from sperm and eggs, to larvae and adults. At each stage corals can potentially be put “on ice”, including the all-important microscopic algae which grow inside corals, providing nutrition and keeping them healthy. More research is needed to determine how cryopreservation can be most successfully done at each life stage.

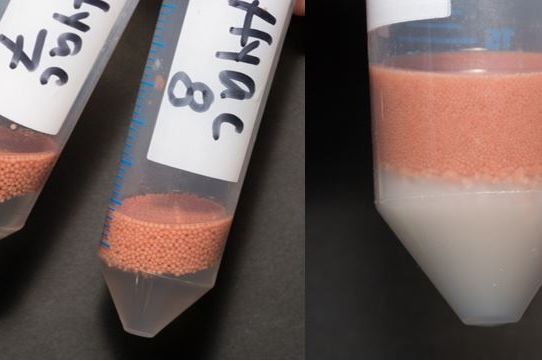

Coral egg and sperm bundles after collection (left) and after the sperm and eggs are separated (right). Credit: R. J. Hobbes

#How does cryopreservation help restore reefs?

Cryopreservation is already used extensively in agriculture to help preserve out-of-season samples, assist with crossbreeding and to secure genetic diversity.

Research into the technology and methods for preserving corals has been in action on a smaller scale for the last 10 years, via a global cryopreservation network including Taronga's CryoDiversity Bank and the Smithsonian Institution.

Taronga currently has the largest frozen collection of living coral samples in the world, with 30 species from the Great Barrier Reef preserved, including high-value reef-building corals. Excitingly, some species of coral larvae have also been successfully cryopreserved and then recovered, which means they can be used to grow new corals.

Now, as part of the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program, supported and partnered by the Great Barrier Reef Foundation, Taronga’s cryobiologists with partners at the University of New South Wales are aiming to improve coral cryopreservation technology in Australia.

They aim to build a bigger, more diverse bank of frozen living corals that could support preserving biodiversity and growing huge numbers of corals in tanks on land, the offspring of which can then be transported and settled onto damaged areas of our Reef to repopulate it.

Top image: Taronga researcher Rebecca Hobbs conducting experiments to fertilise coral eggs with cryopreserved sperm at the AIMS SeaSimulator. Credit: Dorian Tsai, QUT

#Related

Explainers ·

What is coral spawning?

Explainers ·

Uncovering hidden species with eDNA

Explainers ·

What is biodiversity and why is it so important?

Explainers ·