Project News ·

Solution Exchange 2020

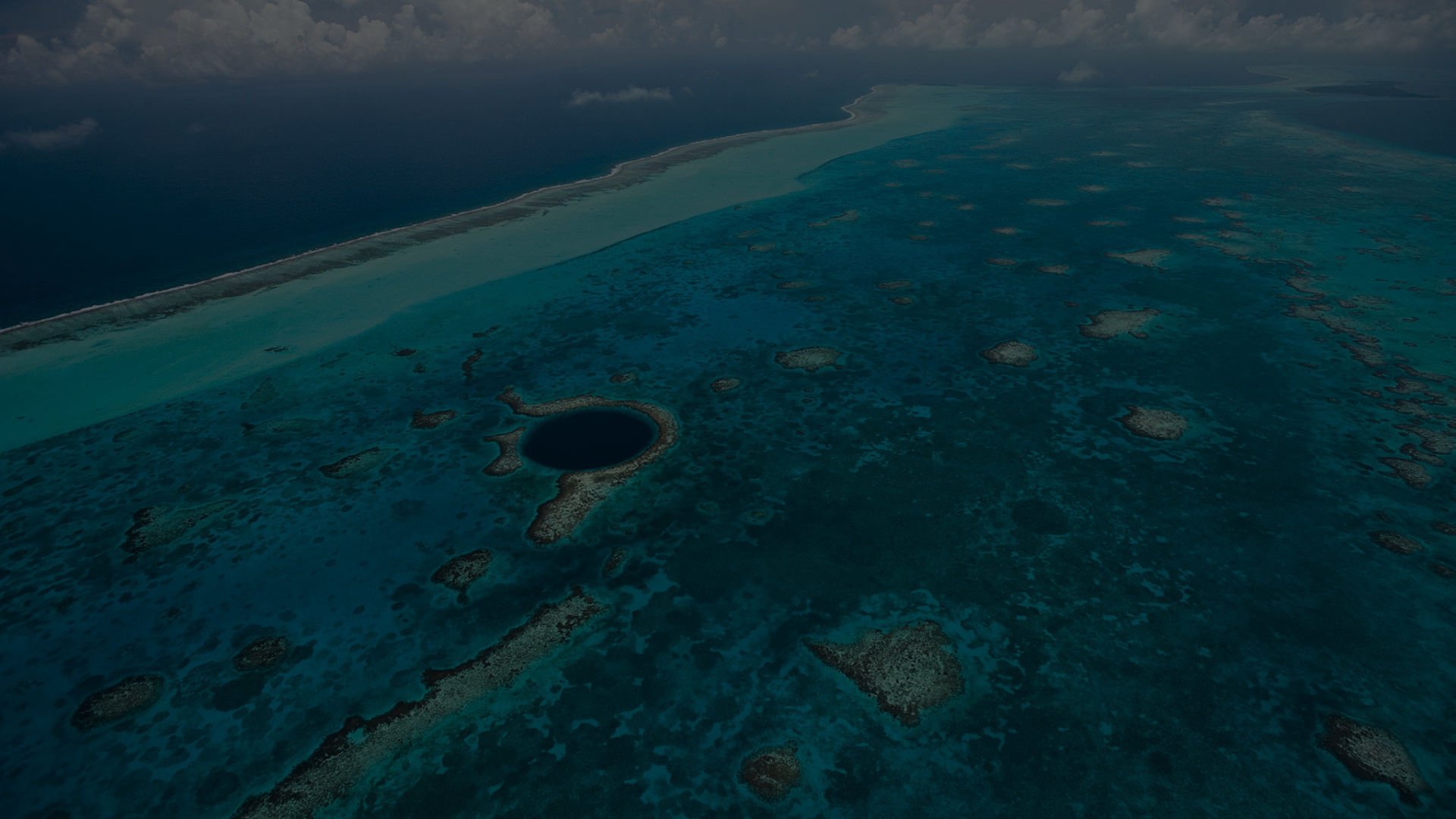

The Resilient Reefs Initiative is a global partnership supporting five World Heritage Reefs, and the communities that depend on them, to adapt to climate change and a combination of local threats.

Here, the Director of the Resilient Reefs Initiative shares learnings from our recent Solution Exchange.

It’s the end of 2020 – people around the world have experienced months of disruption, change and stresses due to a once-in-a-century global pandemic. Building our ‘resilience’ to respond and adapt has become not just a buzz word, but a universally-recognised necessity.

In the year that started with devastating bushfires and the most widespread mass coral bleaching yet on the Great Barrier Reef in Australia, and finished with an equally unprecedented hurricane season in the Atlantic, 2020 is closing out with climate change confirmed as the biggest threat to World Heritage (IUCN World Heritage Outlook 3).

In a year unlike any other, where building resilience – both in people and in nature – has rapidly joined the mainstream lexicon, there’s one program in its third year that is partnering with coral reef communities around the world to build capacity and design solutions to face these massive challenges.

The Resilient Reefs Initiative – pioneered by the Great Barrier Reef Foundation – is a bold new partnership between reef managers, reef communities and global experts to support both coral reefs, and their communities, to adapt in the face of growing uncertainty.

Enabled by the BHP Foundation and partnering with five World Heritage Sites, Resilient Reefs connects local reef managers and communities with a global network – including UNESCO’s World Heritage Marine Programme, The Nature Conservancy’s Reef Resilience Network, Resilient Cities Catalyst and more – to take action in building both reef and community resilience, together and at scale.

#Introducing: Our global Solution Exchange

One of the ways Resilient Reefs drives local impact with global expertise is through the Solution Exchange program: bringing multiple disciplines together to advance thinking and accelerate action on a common problem facing reef managers and communities across the Initiative’s pilot sites.

Over two weeks in November – from socially distanced homes and offices across the globe – more than 100 participants came together for the first Resilient Reefs Solution Exchange, to support two World Heritage sites in preparing for natural disasters that are becoming increasingly prevalent as a result of climate change.

Our partner communities are intimately aware that climate change is altering the landscape of natural disasters – heatwaves and associated coral bleaching, cyclones, flooding and other storms are increasing in severity, and occurring more frequently. And while natural ecosystems like coral reefs are known to underpin almost one billion livelihoods and contribute $10 trillion in services through protecting coastlines from erosion and storms, they are rarely valued or considered as an ‘essential service’ during large-scale disaster planning.

#The Challenge

How can we deliver more integrated and effective planning for climate disasters for coral reef ecosystems and the communities that depend on them?

Our 2020 Solution Exchange—like the Initiative more broadly—sought to identify solutions to this challenge across multiple levels.

1. Providing resources to respond to known threats right now.

2. Driving change in business-as-usual reef management, building partnerships that advance the field of resilience-based management more broadly.

3. Looking ahead, anticipating future threats and opportunities and building local capacities to best manage them.

#What did we learn?

From Mexico to Western Australia we heard wide-ranging solutions and lessons, from innovative insurance policies for natural assets to best practice partnerships within public entities for disaster response and for reef protection.

#Lesson 1

We need to bridge the gap between planning for acute climate events and planning for gradual disasters.

Slowly occurring climate disasters (such as warming ocean temperatures and rising sea levels) have a significant impact on the livelihoods and security of coastal communities, just like acute shocks such as cyclones do. But they differ considerably when it comes to planning, response and recovery efforts. Participants lamented the significant disparity between well-resourced, coordinated and systemic planning efforts for the recovery of infrastructure and services after acute events on the one hand, and under-resourced and often non-existent protocols for the impacts of slower climate stresses on the other.

This reflection spearheaded vibrant discussion around the extent to which traditional emergency management approaches are relevant to the next generation of climate disasters: How useful is best practice cyclone response planning for a bleaching response? This wasn’t conclusively answered – and indeed is part of the work ahead – but it was noted that planning for acute events has the benefit of broad-based political support and ready-made infrastructure for community response and activation that doesn’t currently exist at scale for bleaching events, sea level rise, or other slower-occurring climate disasters.

#Lesson 2

We need to integrate natural ecosystems into emergency management practices.

A common challenge of both acute and gradual climate disasters was the exclusion of natural ecosystems in globally adopted emergency management approaches. Coordinated and systemic emergency management initiated during an acute event focuses on human impact and the recovery of services such as power, water and telecommunications. This emphasis misses the opportunity to address reef recovery as part of broader cyclone response. We know that quick action after a cyclone can increase the likelihood of reef survival significantly, and we know these natural assets are critical for the long-term survival of coastal communities.

A challenge for reef managers is, how do we influence disaster planning decision makers to consider ecosystem impacts as part of planning, monitoring and evaluation of disaster responses?

Fortunately, we heard some good news about how this is starting to change. Recently the U.S. Federal Emergency Management Agency classified several of Puerto Rico's coral reef systems as maintained and engineered infrastructure. This is a significant advancement in the need to value and protect natural ecosystems as central to community protection, and opens up access to additional federal dollars for conservation.

#Lesson 3

We need to normalise communicating risk.

Communities can be afraid to talk about their vulnerabilities, and governments are equally averse to publicising the unknown. This is rational and understandable – yet unproductive in a world where climate change impacts are being felt right now, with unequivocal science supporting a suite of known and irreversible impacts into the future. Sea levels have risen and will continue to rise over time, the world is hotter by at least 1 degree and will continue to get hotter in time – we need to plan for this, in parallel to our global efforts to manage emissions and meet the Paris Agreement. Being honest about the threats we face may catalyse more investment and action. Being quiet will surely do nothing.

#Lesson 4

We need to build the capacity of communities and governments to plan for and respond to climate disasters, no matter the type of event.

Disaster planning typically focuses on specific hazards in isolation, limiting the flexibility and efficiency of response efforts.

The broader disaster response field is moving to adopt multi-hazard, comprehensive recovery plans that can be deployed after a variety of disturbances. Indeed, this has been a major contribution of the burgeoning urban resilience practice over the last decade, spearheaded by efforts like Resilient Cities Catalyst and the Resilient Cities Network. Rather than a static emergency response plan guiding recovery, best in class disaster planning now includes building the capacities of broad sections of civil society, improving coordination and leadership within governance and partnering with neighbouring and related jurisdictional authorities to build redundancy. This systems approach is seen to better prepare communities for a range of disturbances.

And coral reef communities are no different.

Building community capacity may be a linchpin in multi-hazard response planning for climate disasters – a field that is still developing for coral reef communities. But methodologies for mobilising communities in robust response efforts have been tried and tested in Mexico and are now expanding to Micronesia as part of the Reef Brigades model.

#Lesson 5

We need to robustly value our natural assets to appropriately invest in and plan for climate impacts and recovery efforts.

Reef ecosystems underpin the culture, heritage, livelihoods and food security of coastal communities, however – as is so common with our most treasured natural places – market forces and government policies take for granted the ecosystem services they deliver. Natural resource management occurs in isolation to economic development, asset management and community services, and more must be done to educate and engage those working across these sectors and beyond in coastal communities about the protective value and wealth of services that reefs provide.

Indeed, a clear takeaway from the Solution Exchange was the need to better engage diverse beneficiaries of the reef, and create more opportunities to participate in its protection. In particular, participants emphasised the need to advance economic valuation techniques that can better demonstrate both thee values reefs provide as well as the impacts that gradual disasters will have – a crucial step in building the business case for appropriate investment and response. Such techniques should target aspects of the ecosystem that are especially meaningful to decision makers, such as storm protection or fisheries.

Fortunately, that is starting to happen. TNC is moving this work in the right direction, and has developed methods to value and mainstream nature-based solutions. One remarkable example of the market and government recognizing and valuing coral reef ecosystems as central to the functioning of work on the land, is an innovative reef insurance product that has been deployed on the Mesoamerican Reef in Mexico. In this precedent-setting case study, a payout of US$850,000 was made after the 2020 storm season when three hurricanes/tropical storms battered the reef. The feasibility of insuring reefs in Hawaii and Florida has also just been assessed. Research showed that these reefs could be insured against damage from hurricanes and also in the case of Hawaii against bleaching and sedimentation from storm water runoff. Finally, a forthcoming study by Deloitte Access Economics has found that the Ningaloo Reef contributes $110M in economic value and 1,000 full-time jobs in Western Australia – an important building block in making the case for greater investment and protection of this critical asset.

At a more global level, a recent report by the Paulson Institute, Cornell and TNC outlines a range of policy actions governments can take to address the market failures driving global biodiversity loss.

#Lesson 6

Data and modelling limitations are a barrier to effective planning and response.

While crucial in order to predict climate disaster impacts and develop response plans, there are currently significant limitations to existing data and modelling available for climate impacts and disasters – particularly for coral reefs.

In practice, this has meant that despite bleaching being one of the most existential threats reefs face, reef managers routinely receive conflicting bleaching outlook reports from different models for the same season.

Even with the most robust recovery plans in place this inconsistency in predictions means reef managers and communities are unable to take action until an event is well underway.

Greater investment is needed in bringing together the academic and practitioner communities to ground truth and improve on modelling. The Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program is an excellent move in that direction, seeing academic and practitioner groups working together on reef restoration projects such as the Cairns-Port Douglas Reef Hub in development.

#Where to from here?

The impacts of climate change have grave consequences, and it is easy to feel like the decks are stacked against us. But the Solution Exchange revealed a unique and important opportunity.

Resilient Reefs partners with two of the most pristine reefs in the world: the Ningaloo Coast and the Lagoons of New Caledonia are two World Heritage sites that have escaped mass coral bleaching events to date. But neither has a bleaching response plan in place.

The Solution Exchange and the lessons highlighted above provide the Resilient Reefs’ network with a roadmap for how to support these communities and managers as they prepare for and respond to one of the severest threats these ecosystems face.

Next year, these two pilot sites will release comprehensive strategies for building the resilience of their coral and human communities. We look forward to sharing what a new approach to resilience-based management can deliver and to engage with communities around the world on bold action for a more resilient future.

This year has certainly reinforced how much we need it.

Amy Armstrong

Director, Resilient Reefs Initiative

Amy is an urbanist and conservationist, resilience-builder and problem solver. She brings to GBRF substantial experience partnering with non-profit, public, research and philanthropic organizations to design ambitious programs with significant social and environmental impact. Amy leads the Resilient Reefs Initiative – an AUD$14M global effort working at the intersection of community development and ecosystem recovery, partnering with UNESCO coral reef sites to build the resilience of their ecosystems and the communities that depend on them. This work draws on her previous experience helping to design and lead The Rockefeller Foundation’s 100 Resilient Cities initiative – a USD$164M effort to transform how cities understand risk, engage their residents, and plan for the future. Prior to this work, she helped lead and grow two applied research centers at New York University, bridging research and policy to help cities make evidence-based decisions that deliver more equitable outcomes. Additionally, she has experience working for local governments and non-profits on program development, strategic planning, external affairs and policy research and analysis. She is an agile facilitator across sectors and cultures and bring a rigorous approach to helping organizations clarify their strategy and translate it into impact.

#Related

Project News ·

Community at the forefront of Reef water quality protection

Project News ·