People of the Reef ·

Justine O’Brien: ‘I want to ensure the next generation have the role models and knowledge to thrive’

Reproductive Biologist Dr Justine O’Brien is inspired by the diverse international network of scientific researchers, First Nations, and community that she works alongside to protect not only our Great Barrier Reef, but coral reefs around the globe.

Travel several thousand kilometres south from Australia’s Great Barrier Reef to Cammeraygal Country on Sydney’s Lower North Shore, you will find the beginnings of a new coral reef. Here, far from home, tiny frozen coral cells quietly wait, suspended in time and animation, inside a very special kind of bank.

“It is one of the largest wildlife biobanks of living cells in Australia. Across its two locations – on Cammeraygal Country at the Taronga Institute in Sydney and on Wiradjuri Country at Taronga Western Plains Zoo in Dubbo - there are thousands of samples from more than 85 species. Samples from the last remaining megaherbivores on earth including the critically endangered black rhinoceros, to one of Australia’s most threatened amphibians, the southern corroboree frog, reside in the Taronga CryoDiversity Bank, where they are being actively used for conservation. For Great Barrier Reef corals alone, we have nearly 4000 vials of sperm frozen since 2011 across 30 identified species,” says Justine, Manager of Conservation Science at Taronga Conservation Society Australia.

Explainers ·

What is coral cryopreservation?

Justine stands guard over this precious coral cargo, alongside a network of collaborators that span Australia and the globe. Their goal is to not only preserve biodiversity through cryopreservation techniques, but to build a supply of reproductive material that can be used for future reef protection efforts.

To achieve reef restoration at meaningful scale we need to work beyond coral’s annual reproductive event known as spawning. Cryopreservation efforts can help ramp up efforts outside this discrete ‘fertility window’ by building up a large supply of coral ‘stock’ - genetic material like sperm and larvae that make new coral babies - outside of the spawning season. Justine and the team have made incredible advances in the last twelve years, with successful scaled up fertilization protocols and millions of samples now on hand, but they couldn’t have done it without the support and connections that come from interdisciplinary collaboration.

Justine with Taronga’s Coral cryopreservation team Dr Jon Daly (Left) and Dr Rebecca Hobbs (Right) and international collaborator Dr Mary Hagedorn (Centre) and undergraduate student Mariko Quinn from the Smithsonian Institution.

Justine knows firsthand the power of this global knowledge sharing. She spent over twenty years in the United States, working in cryobiology and assisted fertilisation within zoos and aquariums, from the Cincinnati Zoo and Botanical Gardens to co-establishing the Species Preservation Lab at SeaWorld San Diego – a career highlight. It was scientific collaboration that also sparked Justine’s love of the Great Barrier Reef. After attending a Cryobiology conference in Cairns, she got her scuba diving certificate, spent a week diving the Reef and never looked back.

About a year before eventually moving back to Australia she saw Dr Mary Hagedorn speak at another Cryobiology conference on coral biobanking work. “Her world-leading program that started in Hawaii has greatly informed the work at Taronga – little did I know back then that I would be fortunate to be part of those efforts in Australia,” Justine says.

Alongside Coral Cryopreservation project lead Dr Jon Daly, and Dr Rebecca Hobbs, she now works with a diverse group of researchers and Indigenous Partnership teams to build a toolkit of solutions to help the Reef resist, adapt and recover from the impacts of climate change. Known as the Reef Restoration and Adaptation Program (RRAP), they aim to build a bigger, more diverse bank of frozen living corals, particularly those with thermal tolerance traits, that could support growing vast numbers of corals in tanks on land, the offspring of which can then be transported and settled onto damaged areas of our Reef to repopulate it. Justine says that “It provides a rich opportunity for two-way learning, for example around culturally safe practices for biobanking of coral samples from sea Country, and we are fortunate to work with the Woppaburra TUMRA and other First Nations Peoples in this area.”

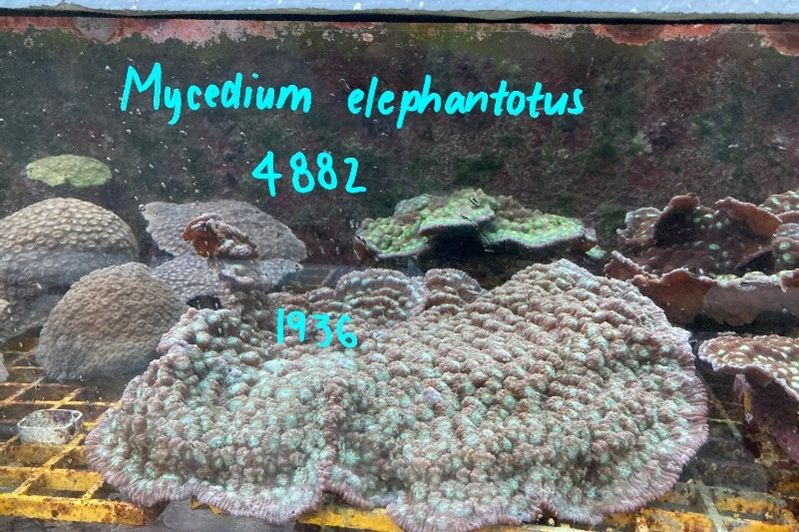

A section of elephant nose coral at the Australian Institute of Marine Science’s National Sea Simulator. Once the coral spawns, Justine and her team collect the sperm for cryopreservation.

Working alongside RRAP teams from the Australian Institute of Marine Science in the National Sea Simulator, Justine first encountered one of her favourite corals - Mycedium elephantotus – AKA the elephant nose coral. For Justine it is a beautiful example of a reef-building coral species that provides crucial habitat to many species of marine life, with a distribution that extends beyond the Great Barrier Reef, across the Indo-Pacific region and into the Atlantic. Unlocking the secrets of cryopreserving and conserving such species, means protecting not only our Reef habitats, but those of other reefs outside of Australia.

“The Reef is driving national and international collaboration at a scale that we have never seen before. Western and First Nations scientists, reef managers, the community, and many others - we can all play a part. The ecological threats and their consequences are immense but as a community there exists real hope.” Justine says.