News ·

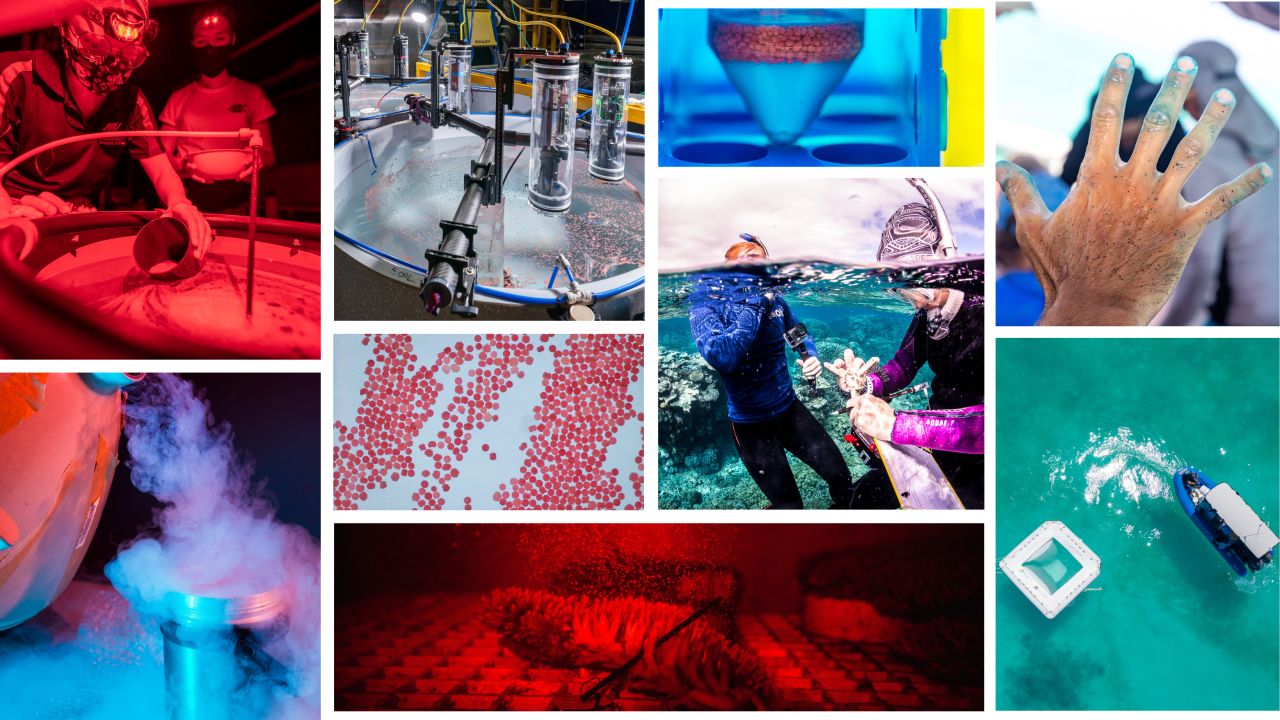

Five technologies getting the most out of coral spawning

Our top picks for game-changing reef restoration tech and innovation.

This past week has seen our Reef quite literally explode into new life for its annual spawning - and the corals aren’t the only ones who’ve been busy. It’s also a critical time of year for our reef restoration teams who work around the clock to research, collect, settle, and grow new baby corals. Often, they’ve got just a few days or hours to get it right – that’s where innovative new tech can help. Here are our top picks for game-changing restoration technologies:

#Inflatable nurseries

Trillions of spawn bundles are released during mass spawning, and yet just a tiny fraction of those will fertilise, form new corals, and survive to adulthood. Pioneering research on the Great Barrier Reef has established a technique to change those odds: specially designed floating nursery pools that collect spawn slicks, culture larvae and then release them back onto the Reef to settle and grow. Conditions inside the mesh-lined pools increase the chance of fertilisation, and their rugged and easily-transportable design means they can be used by non-scientists all over the world.

#Nannycams

Growing large numbers of healthy corals in tanks on land is known as coral conservation aquaculture. The process has the potential to change the face of reef conservation, helping to deliver millions of corals back into the wild and restore damaged areas of our Great Barrier Reef. But there are traditionally a few bottlenecks in the way - not only can coral aquaculture be labour intensive with lots of manual handling, newly-fertilised coral babies are also incredibly fragile in their first few days. That's where a new robotic coral 'nanny cam' could help. Known as CSLICS, it uses AI to remotely monitor and track the growth and survival of baby corals after fertilisation. A game-changer for researchers who can use it to more accurately count, and track corals produced in aquaculture.

#Blue-stained babies

After spawning, coral larvae can travel hundreds of kilometres to neighbouring reefs by hitching a ride on ocean currents. Tracking where they travel is incredibly tricky – but holds the key to understanding how reefs naturally repopulate and where we need to help restore them. A team from CSIRO have solved the problem. They’ve developed a quick, low-cost and non-toxic approach by staining larvae blue and red so that they can be visually tracked as they disperse and settle after spawning. The different coloured dyes last just a few weeks and could be used to differentiate between groups or species, making it applicable to conservation planning and reef restoration experiments in both laboratory and field studies.

Coral spawn and spat stained blue. Image credit: Chris Doropoulos, CSIRO

#Coral cradles

Planting new baby corals is one thing – helping them survive their first year on the Reef is an entirely different challenge. Barely visible to the human eye, young corals are nevertheless a tasty snack for reef fish. Adding to their woes, they also face off against competing encroaching algae and shifting reef rubble. That's why teams of engineers and scientists have been working together to develop and test the perfect ‘cradle’ for these young corals. A robust wave-proof shape, an antifoulant coating and a predator proof design has been shown to improve the survival of corals once they are deployed out into the wild.

#Cryomesh

It may seem like something out of science fiction, yet coral cryopreservation techniques are critical to successful reef restoration. Not only does cryopreserving corals protect their biodiversity, but once reanimated, coral reproductive material could be used to grow millions more corals each year. The challenge has been cryopreserving the successfully fertilised coral larvae - thanks to their size and structure, they are difficult to preserve - but a new prototype may just have solved the problem. The lightweight and cheap-to-manufacture 'Cryomesh’ has successfully frozen and then re-animated Australian coral larvae, without the need for sophisticated cryopreservation equipment like laser warming.